Welding is one of the most important fabrication techniques in motorsports. Today's race shop welders need to be well versed in applying welding techniques to various applications and materials including steel, chrome-moly, stainless steel, aluminum and even exotic materials like Inconel. As there are numerous excellent sources of information on welding, including the American Welding Society, this series of articles is not intended to be a thorough examination of the topic. I would only like to touch upon a few important aspects related to welding as applied to exhaust system alloys such as stainless steel and Inconel as well as aluminum.

Historically, the first welding technique was performed in the middle ages by blacksmiths. Known as forge welding, two pieces of metal were heated until glowing and then hammered together to form a bond. This technique was employed by skilled craftsman through the Renaissance and after. By the late 19th century, electrical arc welding was introduced using carbon electrodes. Over the next many decades, arc welding was perfected by the development of technologies such as coated electrodes and alternating current transformers, Gas Tungsten Arc Welding (GTAW), aka TIG welding, was perfected in 1941 and played a major role in the success of the American war machine.

Historically, the first welding technique was performed in the middle ages by blacksmiths. Known as forge welding, two pieces of metal were heated until glowing and then hammered together to form a bond. This technique was employed by skilled craftsman through the Renaissance and after. By the late 19th century, electrical arc welding was introduced using carbon electrodes. Over the next many decades, arc welding was perfected by the development of technologies such as coated electrodes and alternating current transformers, Gas Tungsten Arc Welding (GTAW), aka TIG welding, was perfected in 1941 and played a major role in the success of the American war machine.

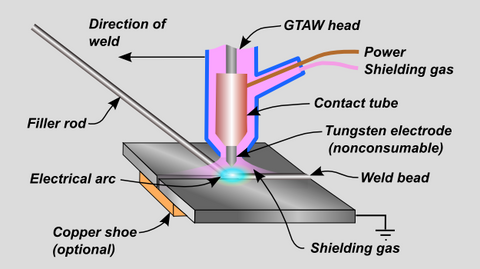

Figure 2TIG welding has also played an immensely important role in motorsports. TIG (Figure 2) is an arc welding technique that utilizes a non-consumable electrode, usually made from tungsten, a separate filler material and an inert gas (argon) shield. It is a manual process that requires tremendous skill, and patience! TIG can be employed with all weldable metals but is the most useful for the welding of alloys such as stainless steel and for thin materials. For this reason, a quality racing exhaust header should be welded using TIG welding. MIG welding should be mentioned as it is a popular welding method due to its ease of use. In fact, it has been referred to as a "hot-glue-gun" by minimally trained production welders.

Similar to TIG, MIG (Figure 3) utilizes an inert gas shield. The electrode/filler are combined in an automatically fed filler wire. MIG welding lends itself to automation and is often used to fabricate production exhaust systems (Figure 4). But MIG should not be used to join the thin sections of tubing used for racing exhausts, sometimes as thin as 0.028". I have seen poor-quality MIG-welded collectors with welding wire protruding into the critical flow path forming "mazes."

The major components of a TIG welder are the transformer, foot-controller, inert gas supply, torch and electrode. The transformer provides the high voltage current needed to heat the base and filler metal. The electric current is controlled by the operator with a foot pedal. The inert gas is supplied by a compressed gas cylinder and controlled by a pressure regulator and flow valve. Argon is most often the preferred gas. The argon gas provides a reactant free zone around the weld and heat-affected zone (HAZ) reducing the formation of oxides that can lead to a weakened weld. Figure 5 shows an otherwise pretty TIG weld where the heat was set too high. Note the large HAZ (bluish area) and the dull color of the weld. Alloys such as stainless steel are prone to the formation of these oxides due to the low thermal conductivity of the base metal that cause the metal to remain hot and reactive for a longer period of time. The argon not only provides an inert atmosphere, but it also aides in cooling the weld joint.

The welding electrode gets very hot and must be water cooled to maintain its integrity. Though the electrode is ideally not consumed, in reality, small amounts of the electrode can deposit on the weld causing contamination. In order to alleviate this, the tungsten is alloyed with various elements, most popularly with radioactive thorium, to increase the operating temperature of the electrode. The thorium can pose an inhalation risk during grinding. Care should be taken to minimize this risk. Newer electrodes are available that do not contain thorium, and should be considered, though many welders prefer the welding characteristics of thoriated electrodes.

The welding torch (Figure 6) is a relatively complex device incorporating the electrode leads, the electrode, water cooling and a gas shield. An important component of the torch is the "gas lens" which focuses the inert gas on the weld. There are various configurations of lenses the selection of which depends on the type of welding to be done. A great deal of skill is needed to be able to accurately control the torch by hand during welding. The welder must also add filler metal to the weld with a TIG rod with his other hand and control the welding current with his foot. To "put-down" a great bead as shown in Figure 7 requires a great deal of coordination, and is why the TIG welder gets paid "the big bucks."

We will continue discussing welding techniques in the next few issues of the newsletter. I hope that you will find this series helpful.